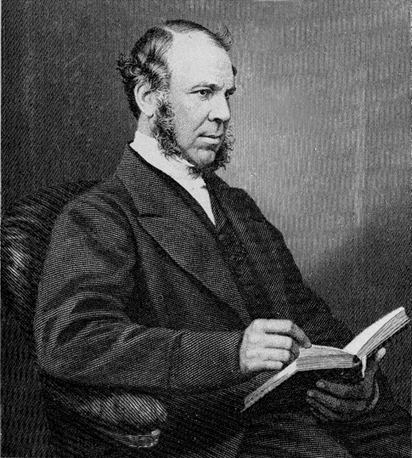

J. C. Ryle. 1879. 324 pages.

Holiness is for Christian readers who desire spiritual instruction that is wholehearted and biblical. This book is an evangelical classic. By “classic” I mean one that has stood the test of time and continues to be highly regarded by evangelical Christian readers. J. C. Ryle’s Holiness argues the biblical meaning of Christian holiness to God and how to grow in one’s Christian faith.

John Charles Ryle (1816–1900) was an evangelical Anglican clergyman whose long ministry spanned virtually the same years as the reign of Queen Victoria (who reigned 1837–1901).

His entry into Christian ministry arose when he—as a young man of a wealthy English family—found himself forced to earn a living due to his family’s fortune was wiped during a bank collapse. He had undergone conversion to an alive and evangelical faith at around the same time, and so he entered the process for Anglican ordination. As a clergyman, he served for thirty-nine years in country churches before becoming the first bishop of Liverpool, where he served for twenty up until his death.

The London Baptist pastor Charles Spurgeon commended Ryle as “the best man in the church of England”, while one of his biographers described him as “a man of granite with the heart of a child” (Eric Russell).

The recently deceased J. I. Packer described him as one who “upheld the Reformation doctrine of grace as found in the Thirty-Nine (Anglican) Articles; he maintained the anti-Romanism of the Articles; he commended the English Reformers, Puritans and eighteenth-century evangelicals as models for both doctrine and devotion; and he spelt out these things in a simple, strong, vivid didactic style, using hammer-blow rhetoric of a most telling sort, which made him not only a valued preacher but also the most popular and useful tract-writer of his day. More than twelve million of his tracts, which number well over two hundred, were sold in over a dozen languages during his lifetime. Their influence on popular Christianity, like that of Spurgeon’s sermons, was incalculable” (preface to Holiness pp. ix-x).

For further reading on Ryles ministry as a prolific tract writer, see the article: J. C. Ryle, “the Prince of Tract Writers” | Crossway

Initially, Holiness was written to correct faulty ideas about holiness that had become current among evangelicals at the time—namely the “higher life movement”. This taught that perfect moral holiness could be attained in this life and that our sanctification was simply a matter of restfully trusting in the Spirit of God rather than by effort and dedication. “Let go and let God” was a popular maxim that expressed the doctrine. Ryle wrote to correct such ideas. But aside from his introductory chapter, his work is largely constructive rather than corrective, aiming to present a positive view of biblical holiness and urge readers to press forward in their faith while resting on the finished work of Christ crucified.

For the remainder of this summary I would like to list the key points of each of the twenty-one chapters, in the hope that Holiness commends itself to Christian readers who are keen to become more pleasing to the Lord in their daily conduct.

Key Points of Each Chapter

“Introduction”: This is the one polemical chapter, in which he asks and answers a series of questions assessing the higher-life-movement doctrine of sanctification:

- Does the teaching that sanctification is by faith alone align with God’s word?

- Is it wise to minimise the Bible’s practical urgings to holy living?

- Does the doctrine of ‘Christ in us’ as taught by the higher-life-movement align with the shape of the doctrine as taught by the Apostles?

- Should a “deep, wide, and distinct line of separation” be drawn between “conversion and consecration” as they do?

- Is it wise to encourage believers to passivity rather than struggle in their abstaining from sin?

To all these questions and more, Ryle argues for the negative.

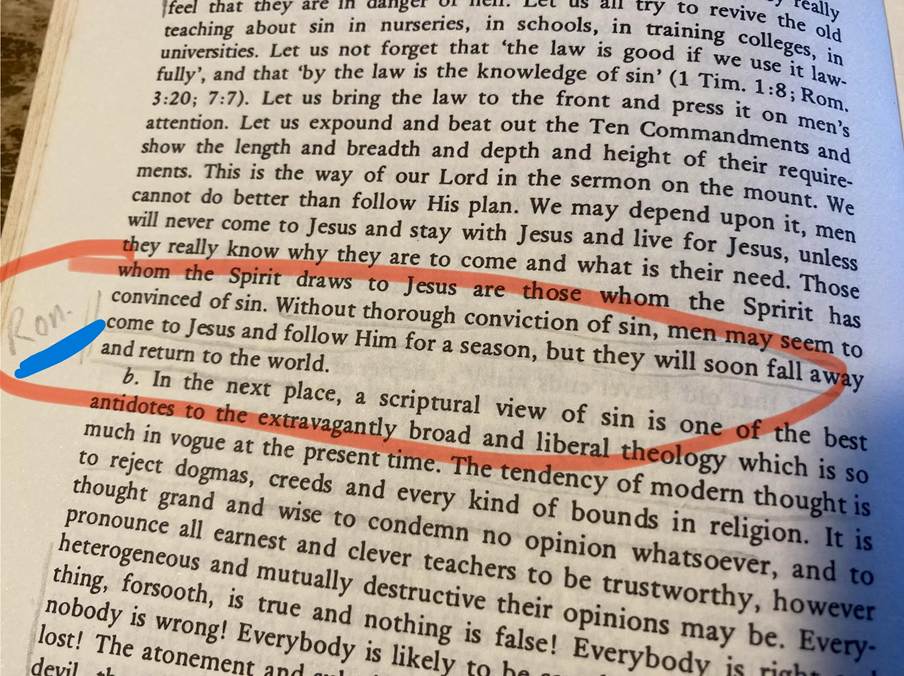

1. “Sin”: [1 John 3:4] This chapter defines sin, describes its origin and extent in the human person, underscores its seriousness and deceitfulness, and offers two encouragements to the reader. The first of these is to personally reckoning with the sinfulness of sin for the purpose of self-humiliation, while the second is to personally grasping with thankfulness the wonderful grace offered to us in the gospel of Jesus Christ. Ryle finishes this chapter by pressing how an appropriate view of sin is a fitting antidote to shallow faith, to liberal theology, to ceremonial churchianity, perfectionist spirituality, and to lazy personal holiness.

2. “Sanctification”: [John 17:17; 1 Thessalonians 4:3] This chapter defines the nature and the visible evidence of sanctification, was well as the ways in which is related to but distinct from justification. It ends, characteristically, with some urging to application for serious readers.

3. “Holiness”: [Hebrews 12:14] This topic is a more practical recounting of the previous chapter. Ryle describes the sorts of persons that are truly holy together with the importance of practical holiness, and asks some pertinent questions and advice to the reader concerning their own attitude to this.

4. “The fight”: [1 Timothy 6:12] This chapter pushes the point that true Christianity and true holiness is by nature, combat. In an age when most people identified as Christians by virtue of being English (for example), this would be hard to swallow. Ryle explains why the fight is one pertaining to the faith we hold, why Paul in this verse describes it as a “good” fight, and encourages his readers to manfully face this fight and to fight with all the resources our faith gives to us.

5. “The Cost”: [Luke 14:28] In this chapter Ryle outlines what it will cost a person to become a Christian, presses the importance of counting that cost at the outset of considering commitment to Christ, and gives some hints on how to count that cost and see that it is worth paying.

6. “Growth”: [2 Peter 3:18] This chapter defends and describes the reality of religious growth in those who have converted to Christ, and then sets out how we can commit to growing in grace.

7. “Assurance”: [2 Timothy 4:6–8] Ryle here emphasises and explores the fact that Christians can have assurance of their salvation and that they are loved by God the Father in Jesus Christ. This was (and is) a hallmark of evangelical spirituality, over against other forms of Christianity in Ryle’s day. He also discusses the fact and reasons why some Christians may not feel this assurance (and yet still be loved by God).

8. “Moses – an example”: [Hebrews 11:24–26] This chapter draws lessons from the example of Moses. Moses forfeited certain privileges and chose what seemed a worse lot in life. He made this choice because of the faith he had in God. From this example, Ryle proposes some practical lessons for Christians to take heed of.

9. “Lot – a beacon”: [Genesis 19:16] The patriarch Lot serves also as an example, but as a negative one whose choices should be avoided rather than copied. This chapter explores what can be known of Lot and considers why he might have “lingered” when told to flee from Sodom, and what it cost him.

10. “A woman to be remembered”: [Luke 17:32] This chapter takes Jesus’ words to “remember Lot’s wife” who looked back when instructed not to. In this chapter Ryle considers the privileges she enjoyed, her sin, and God’s judgement on her. All these are instructive for Christians who might consider turning back on their religious commitments and earliest love of God.

11. “Christ’s greatest trophy”: [Luke 23:39–43] This chapter is about the repentant criminal crucified next to Jesus. From this story Ryle illustrates several things: Jesus’ power and willingness to save sinners, the fact that “11th hour” conversions do not always happen, the fact that the Spirit moves through the same processes in both sudden and slow conversions, and the contention that believers enter into Jesus’ presence immediately after death.

12. “The ruler of the waves” [Mark 4:37–40] Ryle in this chapter draws some lessons from the story of Jesus stilling the storm. He points out that we still suffer troubles in our life on earth, discusses the true humanity of Jesus, the spiritual weaknesses that remain in true Christians, and the power and patience of Jesus Christ for and with his people.

13. “The church which Christ builds” [Matthew 16:18] This chapter delves into the nature of the church, its builder, its foundation, its enemy, and its security. It is noteworthy that Ryle acknowledges that churches in England other than the Church of England (which he was part of) can nonetheless be faithful parts of the one true church.

14. “Visible churches warned” [Revelation 3:22] In this chapter Ryle considers the pointed words of Christ in the seven letters to the churches at the beginning of Revelation, and suggests how they challenge churches of the present—whether Anglican, Presbyterian, or Independent. He asks readers to pay attention to Christ’s warnings and promises regarding church doctrine and practice.

15. “‘Lovest thou me?’” [John 21:16] This chapter considers the feeling of true Christians towards Christ, and how it makes itself known. Ryle fleshes out the reality of the love we have for Christ.

16. “Without Christ” [Ephesians 2:12] Ryle takes opportunity in this chapter to describe the state of those who are unconverted. Ryle discusses what it means to be “without Christ” and what they will lack in this state.

17. “Thirst relieved” [John 7:37–38] This chapter delves into the promise of living water that Jesus offers.

18. “Unsearchable riches” [Ephesians 3:8] Gospel ministry is the key focus of this chapter. Ryle considers Paul’s estimation of himself, his estimation of his role as a missionary-preacher, and his estimation of the subject of his message: the unsearchable riches of Christ.

19. “Wants of the times” [1 Chronicles 12:32] Ryle hoped that he would be like the men of Issachar, who “had an understanding of the times” that they lived in. Ryle here proposes what he thought were the acute spiritual needs of his age: “a bold and unflinching maintenance of the entire truth of Christianity”, “distinct and decided views of Christian doctrine”, “an awakened and livelier sense of the unscriptural and soul ruining character of Romanism”, “a higher standard of personal holiness … and practical religion in daily life”, and a “more regular and steady perseverance in the old ways of getting good into our souls.”

20. “Christ is all” [Colossians 3:11] This chapter explains the centrality and totality of Christ in the purposes of God, the Bible, true Christianity, and in heaven. Ryle finishes this chapter with pointed questions and directions to his readers in this vein of thought.

21. “Extracts from old writers”. This chapter includes some lengthy excerpts from Puritan-era (1600s) writers: Robert Trial on justification, and Thomas Brooks on holiness. Ryle believed these were too good not to share as they stand on their own, and readers who care deeply about these topics will no doubt agree.

As I said at the outset, Holiness is for Christian readers who desire instruction in Christian growth that is wholehearted and biblical. It is not snazzy and exciting, but it is certainly comparable to an old-fashioned, wholesome and hearty British dinner of roast beef and potatoes. This has plenty of nutrition for hungry souls, and is as suitable for Christians serious about their faith as proper food is to a professional athlete or a physical labourer. The rather bony outline I have given fails to do justice to these essays, each of which warrants thoughtful self-application.

Readers have benefited from this book for well over a century and its continued republication points to its enduring popularity today. It might be firmer food than what many today are used to, but I myself commend it as well worth the effort.

Holiness is available from Fishpond for NZ$46 (December 2025). Alternatively, you will find second-hand copies or e-book versions for a much lower price.

Sermon Biography by John Piper: “The Frank and Manly Mr. Ryle” — The Value of a Masculine Ministry