Frederick Van der Meer. Sheed and Ward. 1961. 585 reading pages + endnotes.

The North African Christian leader Aurelius Augustine (354–430) is well known for his theological writings. Their impact has been monumental on the development of Western Christianity. But he is much less well known for his primary role: that of a bishop and pastor in the small town of Hippo in modern Algeria, near to the larger city of Carthage. Primarily, the famed Augustine was a regular overseer and shepherd of a church, busy with its routine tasks and the joys and troubles that regular care and contact with people bring in pastoral ministry.

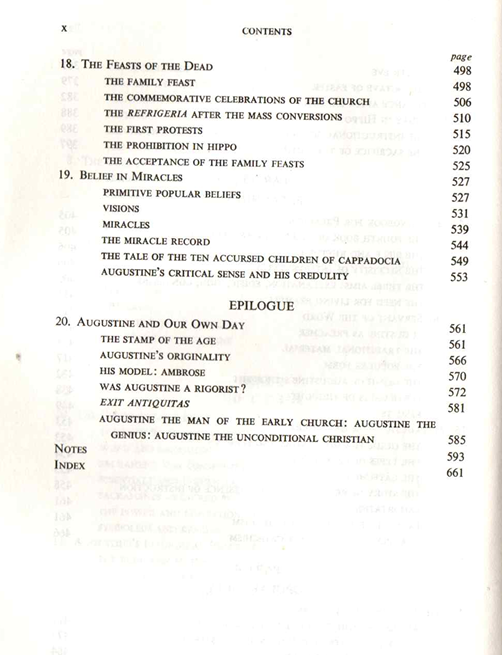

Augustine the Bishop offers a comprehensive view of Augustine’s lifetime of work as a pastor. This book is not (quite) a biography. Readers wanting a biography should find a copy of that by Peter Brown. This book does not cover Augustine’s childhood or his fascinating and fraught journey to Christian conversion. Nor does it explore his polemics with Pelagius or his musings on the doctrine of the Trinity. Instead, Augustine the Bishop focuses on his day-to-day work in and around his church.

As the author himself explains:

“What many readers of Augustine’s writings do not realize is that his simple cathedra (preacher’s chair) was more important to him than his pen. It was the needs and cares of ordinary Christian folk that supplied both the matter and the manner of his loftiest writings, so that the main function of his genius was to serve the pastor of souls.” (p. xvii).[1]

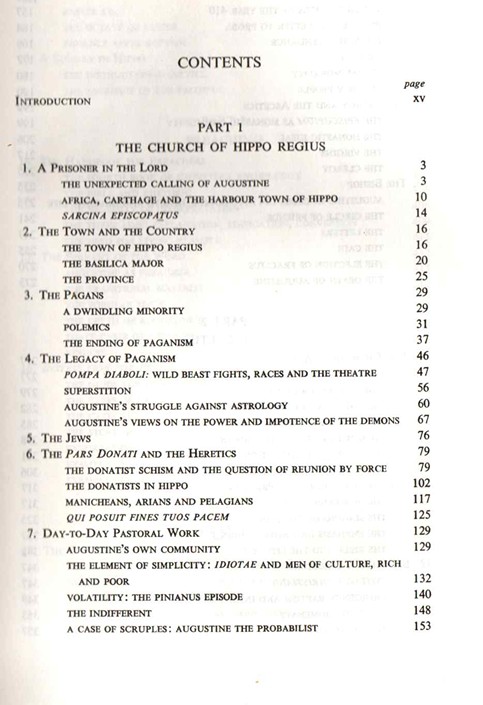

Part One of this book explores the setting of the church in Hippo. It includes Augustine’s entry into church ministry, describes the rustic town and its countryside, and its basilica (i.e. church building). Much attention is given to the other contenders for the hearts and minds of the people of Hippo: the remnants of classical paganism, astrology, the Jews, the violent Donatist sect, and several heretical Christian sects. This large initial section (some 260 pages) also describes miscellaneous features of the life of Christians in that time and place, and how Augustine addressed these as well as of the habits and practices of Christian clergy. Augustine’s response to the sacking of Rome in 410 is covered too. It also describes Augustine’s appearance and simple dress. For anyone with an interest in exploring the “social history” of everyday life, this will be a delightful section to read. It is brimming with all manner of stories and descriptions of this slice of the ancient world.

Part Two is about “The Cultus”, i.e. the practices of Sunday church gatherings, the initiation of new converts, and how church was understood theoretically.

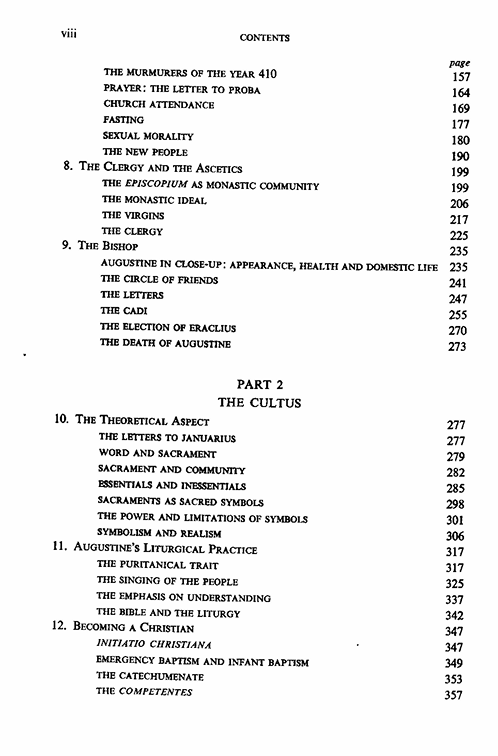

Part Three is about Augustine’s practices of preaching and catechesis (instruction in the faith). I particularly enjoyed hearing of the lively to-and-fro that happened between the preacher and people. Many congregants knew Augustine’s go-to verses and would chime in to finish his sentences when he repeated his favorite texts.

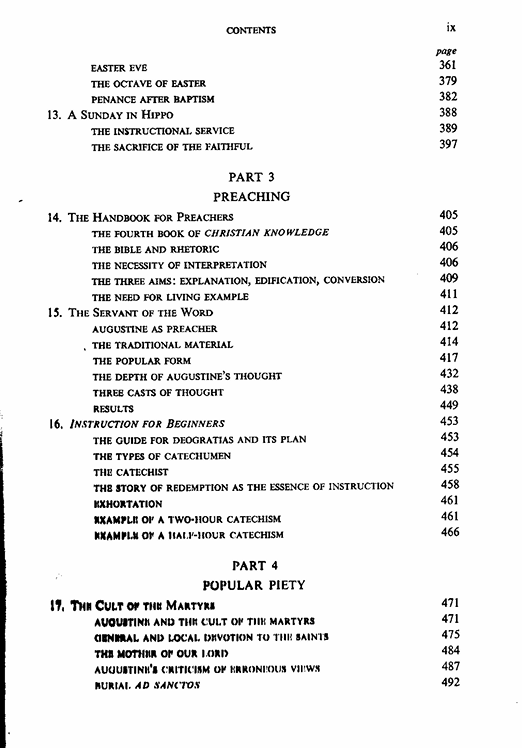

Part Four recounts the practices of popular piety held by many of the people of North Africa, with or without church leaders’ approval for them. These included the commemorations of Christian martyrs and veneration for the saints, burial practices, the festivals for the dead, and the beliefs in miracles and the retelling of popular miracle stories.

The primary sources for this book were picked mostly out from Augustine’s voluminous writings, and from archaeological digs in North Africa. Other ancient written sources are unfortunately quite scant. My repeated checking of the endnotes for sources led me to expect that Augustine’s sermons, letters, and expositions on the Psalms are particularly illuminating. Hopefully I’ll get around to reading them one day.

The book is quite lengthy at around 600 pages of smallish print, but it is not (too) laborious. It could be likened to a rather long hike but one without too many hard hills or oppressive weather—it requires more patience for the journey than determination for the challenge. Much of the book is made up of numerous anecdotes and sermon sections, which make for easy reading if not scholarly analysis. Despite this, the author is not uncritical of Augustine and gives his own intelligent assessments. I appreciated hearing this author’s voice regularly in the book even if I didn’t agree with him. He also gives occasional smatterings of French or German which the translators did not translate into English, and allusions to less-well-known Continental European philosophers and poets that I had never heard of (the author was a Dutch Roman Catholic who did not write in English).

Readers interested in the possibility and practice of being a “pastor theologian” will find this lengthy book a delightful if sobering picture of the realities of church ministry. Much of it is more mundane than theology students might like: not all people have the intelligence and patience for deep doctrinal instruction. Many inquirers or church members are slow to learn, limited in capacity, and stubborn in their character flaws! But Augustine loved God and he loved God’s people, and so for him the duty of the care of souls was a privilege he gave careful attention to. And as any long-serving pastor-theologian could testify, it is such ministry that becomes the forge for the theology that really forms and shapes God’s people.

Theologians whose hearts beat likewise will find in this portrait of Augustine the Bishop a kindred spirit.

[1] Of all his greater works only that on the Trinity was not written in response to pastoral needs.

This book is out of print and no longer sold new, but here are a few places you can locate a copy:

- Borrow the E-book online: augustine the bishop : f. van der meer : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive (if you want to read a 600 page book on a laptop!)

- Hard copies are available in quite a few NZ university and Bible College libraries: Augustine the bishop : the life and work of a father of the church | New Zealand Libraries

- Second hand on Amazon: Augustine The Bishop: The Life And Work Of A Father Of The Church: Meer, Frederick Van Der: 9780722012154: Amazon.com: Books

- Second hand from Abe Books: Augustine the Bishop by Meer – AbeBooks